Neuropower

by: Warren Neidich

Published in: Atlántica Magazine of Art and Thought #48-49, 2009

Neuropower in Atlantica

DARE | Warren Neidich

“Did she do it or – or not? One of the 2008 American presidential campaign’s central controversies concerned a dubious list of forbidden books. John McCain’s vice presidential candidate, Sarah Palin, was supposed to have compiled the list in her capacity as former mayor of the small Alaskan city of Wassila. The aim of the compilation was allegedly to remove the listed titles from the local public library. Palin resolutely denied these accusations on several occasions. Her opponents, however, were not convinced. If the accusations were true, it would have been a clear case of censorship. If they weren’t true, then at least the existence of the hit list circulating the Web evidences a canon of disagreeable yet popular books – one that the conservative, evangelical American Right would love to have banished from public libraries.

Exactly this explosive constellation is the starting point for the procedural installation “Book Exchange,” which the artist Warren Neidich – born in 1958 in New York, now working and living in Berlin and Los Angeles – showed last summer at the Horowitz Gallery in East Hampton, on Long Island. East Hampton is not just a prime destination for recreation-seeking New Yorkers; ever since Jackson Pollock settled there, in the 1940s, it has been the artists’ and art-collectors’ colony on Long Island par excellence. Not a bad place to observe “Book Exchange” in real conditions.” – Nicole Buesing and Heiko Klaas

Highlights (2008-10)

Neuroaesthetics Conference (2005)

Full texts published in the fourth issue of the Journal of Neuro-Aesthetic Theory on artbrain.org

Conference Sessions

First Dialectic: Edges of the Envelope | Chair: Charlie Gere

Brian Massumi

Ready to Anticipate: Pre-emptive Perception and the Power of the Image

D.J. Culture and Sampling | Chair: Daniel Glaser, Mental Projections

Paul Miller, a.k.a. Dj Spooky, Rhythm Science

Respondents:

Kodwo Eshun

The Affective Logic of the Sound File in the Age of the Global Sound Archive

Drugs, Altered States of Consciousness and Cultural Production | Chair: Warren Neidich

Diedrich Diederichsen

The Heuristics of Psychedelic Enlightenment

Respondents:

Margarita Gluzberg

How to Get Beyong the Market - Transubjective Reality in the Salyia Divinorum Forest (Let the Crowds in)

Martina Wicklein

The Brain on Drugs

Curating the Neuro-Sensorial-Cognitive | Chair: Andrew Patrizio, Neuro-Curo

A Discussion with:

Chloe Vaitsou

Synaesthesia, a Neuroaesthetics Exhibition

Isabelle Moffat

This is Tomorrow: A case of Psychoneural Isomorphism

Art Praxis: Part 1 | Chair: Charlie Gere

Joseph Kosuth

Celebrating Contingency

Respondent:

John Armleder

Pertinent Works

Art Praxis: Part 2 | Chair: Scott Lash

Scott Lash

Introduction to Panel Art Praxis

Olafur Eliasson

Uncertainty of Colour Matching and Related Idea

Respondents:

Beau Lotto

The Postmodern Brain

Jules Davidoff

Colour Categories as Cultural Constructs

Israel Rosenfeld

The Question of Plasticity

Architecture and Architectonics | Chair: Deborah Hauptmann

Marcos Novak

Alloaesthetics and Neuroaesthetics: Travels through Phenomenology and Neurophysiology

Respondents:

Andreas Roepstorff

Functional Architectonics of the Brain: Co-evolving Structures of Meaning

Philippe Rahm

Inhalable Spaces

Neuroaesthetics: Process and Becoming

Charles Wolfe

The Social Brain

Armen Avanessian

Aesthetical Theory, Scientific Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art: Contrasting Concepts and Perspectives in Art

Cultured Brain 1 | Chair: Johannes Menzel

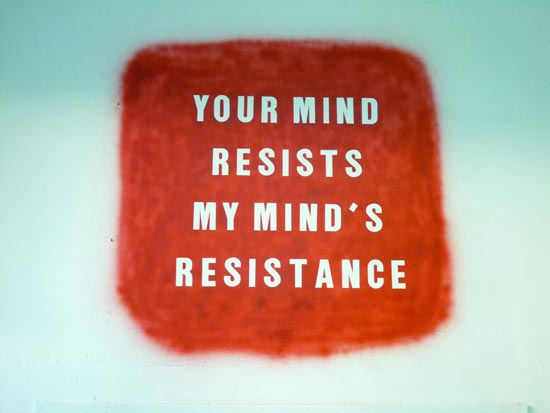

Warren Neidich

Resistance is Futile

Cultured Brain 2 | Chair: Howard Caygill

Charlie Gere

Can Art go on without a Body?

Respondent:

Lucy Steeds

André Leroi-Gourhan: Neuroaesthetics?

Cultured Brain 3 | Introduction: Warren Neidich

Barbara Marie Stafford

Soma-Aesthetics, Constructing Interiority

Respondent:

Sarah Maharaj

From the Afterlife to the Atmospherics reassessing our basic assumptions

Body-Wall Maple Cottage (2005)

Body-Wall Maple Cottage

2005

In this work a false wall made out of plywood wound its way around an abandoned cottage first blocking the staircase, then creating a false passageway that began at the original door and continued until the front wall of the house itself. This new space created a hybrid space in-between the original house and the new wall and thereby set up a dialectic between past and future with the spectator mediating between the two. The visitors were transformed into performance artists and actors and were made aware, by a small light, of a viewing device through which they were meant to look to see an enclosed domestic space reminiscent of the places of inspection so often used by Sherlock Holmes. The optical pathway for this inspection was a hole cut out of the eye of an old portrait painting that hung on the inside of this simulated domestic space. This opening in the painting was lined up on one hand with a hole in the wall itself and on the other with the viewer’s eyes. Together they created a machinic assemblage that was aligned with a mirror hung directly across the room which reflected the antique painting, mentioned above, and the eye of the viewer that through his or her participation was now part of. The viewer’s eye, as it looked through the painting from behind the wall, now became part of the painting itself. The hidden passageway became an uncanny space in which the fragmented viewer through a transformational process of the experience of becoming an actor in this architectural scenario became a whole body again not as himself but as a painting with all the meanings pertaining to the nature of portraiture itself.

When You Look East You Are Already Looking West (2009-10)

Brainwash 2 (2009)

Silent: A State of Being (2004)

Some Cursory Comments on the Nature of my Diagrammatic Drawing

The diagram is indeed a chaos a catastrophe but it is also a germ of order or rhythm. It is a violent chaos in relation to the figurative givens, but it is a germ of rhythm in relation to the new order of the painting. As Bacon says, it “unlocks areas of sensation.

Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, Gilles Deleuze

The diagram or abstract machine is the map of relations between forces, a map of destiny, or intensity, which proceeds by primary non-localizable relation and at every moment passes through every point, or rather in every relation from one point to another.

Foucault, Gilles Deleuze

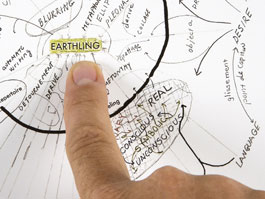

I approach the Earthling Drawing that is tacked to my wall. It is at some distance now and what I see is a multicolored abstract drawing that covers the paper with lines, marks and points distributed unevenly. Several, separate areas are demarcated like small continents. These parts, of which there are four, have developed over the past 8 years. They have been drawn, overdrawn, redrawn, extended and edited. As such, the drawing is an impermanent condition of a still evolving process! The first part is called The Cultured Brain Drawing and fills the space in the middle right hand section. It looks like an amoeba with pseudo pods. The second part is called The Global Generator and it is funnel shaped and situated at the bottom. The third section is called The Becoming Brain Drawing and is found on the far left. Finally, The Earthling Drawing is found in the upper right hand corner and was the most recent addition.

As I continue my approach I realize that there are words that adorn its’ arabesque forms. I first point and then deliver my finger quite randomly to a location towards the center left center. This initial touch begins a drifting process in which my finger tip is a compass navigating a route or root to other locations and places as a tracing. My finger for instance my finger alights first in The Cultured Brain Drawing on Culture 1 (Extensive Culture). It then moves up along a tracing connecting it to Culture 2 (Intensive Culture). The arrow is bidirectional and connotes that each is symbiotic and contained in the other as nested symbolic gestures (see figure 2).

Intensive Culture (Culture 2) is the product of an ontologic process that emanates from Culture 1 (Extensive Culture) and is defined by a multiplicitous, non-linear, rhizomatic processes, immaterial labor as a virtuoso performance and the conditions of the social brain. It has supplanted its predecessor Culture 1 (Extensive,Culture) defined here as a set of conditions which has been formed according to a different set of coordinates and logics. Ones, which are equally divisible, linear, narrative in which labor concerns the production of a real objects tethered to the actions of the physical body. Each is situated in a diffuse milieu of The Cultured Brain Drawing signified by random colored dots made with the end of a blunt magic markers, which are diffusely distributed throughout. Closer inspection unveils a series of flowing multicolored lines swooping in from the bottom left where after entering the inside of the drawing they seem to fragment.

By a reverse tracing, the finger follows the multiple multi-colored curved lines back down towards an upside-down, cone-shaped funnel situated below. I refer to this part of the drawing as The Global Generator. The cone is divided into two parts. The top is the generative source of the colored lines and upon close inspection one can see that they are labeled according to the immaterial relations such as the social, political, historical, economic, psychological and unknown that they designate. Each, in itself, is in constant flux and is caused by the incessant shifting of internal differences which form its structure constituted by, for instance, the logic of the symbolic conditions that give it meaning. Moving the eye along each sinewy strand -in fact the eye has learned to follow the finger- one begins to notice lightly traced eddies and whirlpools that represent feedback and feed-forward circuits that link all the relations together and which through a series of tight junctions, open conduits which allow for the exchange of internalized elements, allowing information to diffuse from one relation to the other, producing differences that need to be adjusted to.

Forming the substructure of the funnel are a series of labels like, Ethnocape and Mediascape that refer to the mutating conditions of culture in the global setting adopted from the work of Arjun Appadurai Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. They form the foundation of the cultural shifts from Culture 1 to Culture 2.

I resume my drift and now move my finger again upward and rejoin the The Cultured Brain Drawing. My finger tip, like a vagabond circulates throughout the terrain of the inside, finding shelter under its nested regularities labeled Plastic Arts, Architecture, Technology and The Film Arts. Like the Visual Culture they together help to produce each other, in a condition of flux as they respond to the same immaterial conditions. Each attempts, as best it can, using its own histories, performances, apparatti, techniques and materials to make its own image. An image that is a present and past tense simultaneously. An image of the past, which is reflected in the history of all its past images, as each travels along its own journey of time. How design of jewelry and religious artifacts used in burial rights has changed since the time of the Cro Magna! In the present tense, each is the consummated activity of the immaterial relations that it embodies and that, like a mirror, reflects back to be cogitated by the subject as observer who, witnessing the differences in that ontology, understands the differences inherent also in himself and herself. But, as an assemblage as constitutive elements in the much larger apparatus of visual culture, these separate aesthetic-producing activities together, constitute a non-linear, emerging superstructure that is more than the sum of its parts. This superstructure digresses away from an equilibrium condition; entropy plays havoc on its component parts as well as on itself, it releases latent potentialities, add that defines each epoch. Thus, who have ever imagined that Surrealism would emerge from the Bowels of Impressionism and that the New Figuration of, say, John Currin or Elizabeth Peyton in the early 1990s would have developed from a culture obsessed with conceptualism and abstraction. And, today, the mutating social political historical economic and psychological conditions of, for instance, Post-Fordist Labor in the Age of the Multitude and the Empire constitute art works, built spaces and buildings, films that respond to those mutating conditions producing the works of artists like Liam Gillick or Carey Young and architects like RUR and Zaha Hadid.

My finger, like a mouse on a computer screen, engages the drawing again now in a random walk through this information map and alights again on Culture 2 and then moves through a portal, into an area called The Secondary Repertoire just above and to its left. The Secondary Repertoire is a condition of the nervous system which results from its reaction to the environment, of which culture plays an important role. As a result of the conditions of intrauterine development and the genetic contribution of your mother and father, the brain, at birth, is made up of elements that are ready to operate in any environment that the baby might find itself. These, you might say, are pre-determined, like the sucking reflex and the beginnings of sight. I might say, however, that this Determined Brain is very underdeveloped compared to, for instance, a baby horse, that at birth can already walk. Nonetheless, there is also a Becoming Brain, one that has a potential to be modified. A brain in which large areas have not yet been organized and that are ready to meet the specific demands, within reason, that it is born into. According to neuroscientist Gerald Edelman, in his book, co-authored with Giulio Tononi, A Universe of Consciousness, the brain is made up of a large population of variable nervous elements some of which can become selected by the conditions of the world that it finds itself in. Neurons -the basic building blocks of the nervous system and neural networks- that are selected, operate more efficiently than those not selected for and, accordingly, will out-compete others for the confined and limited space of the brain. The process of, for instance, neural selectionism, combined with the brain's inherent potential for change, called Neural Plasticity, allows for a sculpting of the brain. Each culture provides a metaphor for that sculpting, whether it is the Figurations of Rodin, the Scatter Art of Barry Le Vay or the cacophonous meanderings of Jason Rhodes that call out to the brain in different ways, intensifying different networks and currents and diminishing others. D.O. Hebbs in his famous book of 1949, The Organization of Behavior, states that "neurons that fire together wire together.” in this context, this adage becomes "Network conditions in the Real-Imaginary-Virtual Interface sculpt Network Conditions in the Brain." These new forms of interconnection reflect the cultural conditions and the immaterial relations, as we already saw, produce it. The mutating conditions of the assemblage of Networks as they are produced by the mutating conditions of culture create new dynamic pathways for thought and the imagination. In fact, each culture produces what Deleuze called 'noo-ology,' the history of the Thought Image through its inflection in the intergenerational conditions of the selected brain and the psychological and philosophical thoughts that emerge.

As we have mentioned already, Culture 2 directly contacts the Secondary Repertoire through a portal cut in the flesh of the diffuse milieu of Cultured Brain Drawings Microscopy. It is connected to the Primary Repertoire from which it emerges. The pleuripotential Primary Repertoire is the brain at birth or shortly before. It is the end point of Develpmental Selection, which we mentioned above, and produces the variable population of neurons that Culture 2 can now act upon. It is a node that indirectly connects the other parts of the drawing; to its upper right the Earthling Drawing and to the left the Becoming Brain. The Earthling Drawing delineate the conditions of the unconscious and the pre-individual, where the new logics of global Capitalism, according to Antonio Negri and Maritzio Lazzarato, are now focused. In the transformation of labour to its current Post-Fordist condition, noo-politics, namely the ensemble of techniques of control exercised on the brain and aimed at memory and attention is the order of the day. Through the 'distribution of sensible', the partage du sensible as Jacques Ranciere has defined it in The Politics of Aesthetics, sovereignty creates a series of laws and dispositions that establishes the modes of perception, that is, the set of perceptual horizons, a system of self-evident facts of perception that delineate what can be heard, said, made and done. Those distributions are very different in an Intensive Culture and in an Extensive Cuture. The order and sequencing of those stimuli, especially as they are generated in built space, have implications for the history of the thought image and the becoming brain. In the present Intensive Global Culture, the expanded role of capital in the generation of the general intellect consortiums of media giants, cognitive neuroscientific research assemblages, the military, advertising firms, polling interests consciously or unconsciously have littered Cultural Visual/Haptic Landscape with very sensational stimuli. Paul Virilio has labeled these processed and engineered stimuli Phatic Stimuli to draw attention to their conditions of Emphasis and Empathy, which are produced to call out to the brain and mind of the multitude. Branding would be an example of such a Phatic Stimuli, especially as they circulate in the real abstract conditions of billions of televisions and computer desktop terminals. In the expanded condition of thousands of these phatic stimuli operating together in immanent assemblages forming intensive networks of phaticity, a simulated ecology of meaning becomes possible. This intensive environment is now what calls out to the brain and preferentially selects neurons and neural nets according to its logic. This is one condition of the Earthling as a new Global Subject in the production of the people of the planet Earth. But there is another story.

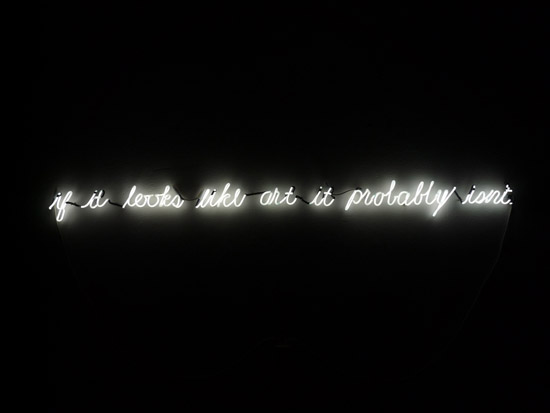

In their most Utopian sense artist, architects, designers, writers and cinematographers, just to name a few, utilize there own methods, apparati, histories, spaces, performances to produce another distribution of the sensible, a Redistribution of the Sensible, that competes with that of the aforementioned Institutional Conditions for the attentions and memories of the multitude. This is the real story of the Earthling Drawing. Art as a form of resistance in which the form(s) of the Distributed Sensibility is the conceptual palate through which new forms of imagination with their potential for difference are transfigured.

The diffuse logic of my now unconscious finger searching for the intense psycho-geographic spaces finds itself, through diagonal and lingering gestures, in the cyclic looped Earthling Drawing. Here is where the dynamis of subjectivity is produced; where the pre-individuals of the singularities reside. Embedded in a spinning vortex of energy relations are a history of forms of that resistance to institutional norms, which constitute the homogeneity of the people. Practices like The Paranoid Critical Method of Salvador Dali, the channeling and theater of cruelty of Antonin Artaud, the Ready-made of Duchamp, the Derive of Gilles Debord, the collage of John Heartfield, the automatic writing of Andre Breton which produce new objects, object relations, space, reactions and virtuoso performances. To these practices could be added the Race, Gender and Class-Based practices that have become critically important in the past forty years. Here, the work of Mary Kelly, Andrea Fraser, Felix Gonzales Torres, Fred Wilson and Valie Export come to mind. These new conditions of the distribution of sensibility, now populated by these other objects emanating from quite different conditions, cause perturbations in the Institutional Diagram and produce adjustment of the minds eye as it scans the visual, auditory and haptic landscape in its daily routines. Through the same process of Neural Selectionism and its affect on the primary repertoire new connections are built; an other Cultured Brain. As such, attention and memory, the building blocks of the conscious and unconscious, are undeniably affected as well. As the world of imagination and fantasy creates the internally mediated stimulation of those and other circuits, neural sculpting and the mind will, though various feed-forward and feedback looping, be affected. Sovereignty in the age of controlling the mind at a distance is hip to the contingencies of the possibility of culture as its competitor. The new war on culture and the differences it produces is taking many forms. From the reduction of funding, to the extended power of the market place, to the new interest in the funding of the what are referred to as the cultured industries, Sovereignty is doing all it can to usurp the power of the artist.

The Neurobiopolitics of Global Consciousness

Neuroscientists say that by peering inside your head they can tell whether you identify more strongly with J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter, say, than with J.R.R. Tolkien's Frodo. A beverage company can choose one new juice or soda over another based on which flavour trips the brainís reward circuitry. Itís conceivable that movies and TV programmes will be vetted before their release by brain-imaging companies.1

In their well known study Empire (2000), social theorists Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt elucidate what philosopher Michel Foucault had already made explicit in the last chapter of his The Will To Knowledge (1976): they once again reiterate and delineate, in Section 1:2 of their text, the different and evolutionary consequences of the disciplinary society and the society of control (to use Foucauldian parlance). On the one hand, the disciplinary society is constructed through a dissemination of social command by diffuse networks of ìmachinic assemblages, to borrow a term from the cultural theorist Gilles Deleuze, that regulate each subject's customs, habits and productive practice.2 Extensive culture (characterised by stable Euclidean geometries, the assembly line, arboreal classification systems such as the taxonomic classification systems of Carl Linnaeus) operates upon the subject from the outside, specifically restricting his or her movements and choices along pre-set paths. Disciplinarity fixed individuals within institutions but did not succeed in consuming them completely in the rhythm of productive practices and productive socialisation: it did not reach the point of permeating entirely the consciousness and bodies of individuals3. On the other hand, the society of control operates within the domain of intensive cultural apparati characterised by the Riemannian spaces, rhizomatic logics and folded temporality induced by the multiplicity of flows that characterise our global world post-internet.4

According to Negri and Hardt, this transition from a disciplinary society to the society of control involves the emergence of what they refer to as 'biopower', which regulates social life from within. By contrast, when power becomes entirely biopolitical, the whole social body is comprised by power's machinery and developed in its virtuality. This relationship is open, qualitative, and affective. Society, subsumed within a power that reaches down to the ganglia of the social structure and its processes of development, reacts like a single body. Power is thus expressed as a control that extends throughout the depths of the consciousness and bodies of the population and at the same time across the entirety of social relationsî5.

Since 1987, the field of neuroscience has seen the emergence of Neural Darwinism and Neural Constructivism, powerful new theoretic tools that have profound implications for how biopolitical systems might instantiate themselves in the neurobiological substrate of the individuals that comprise the social body. Utilising these concepts, I would like to explore the possible mechanism and sites through which we might understand the new potential for biopower, which I am now referring to as the neurobiopolitical: the ability to sculpt the physical matter of the brain, and its abstract counterpart, the mind. I will also show how this process ultimately has very significant implications for imagination and creativity.6

Neural Selectionism / Neural Constructivism

Recent research in neuroscience, most notably the pioneering work of neuroscientist Jean Pierre Changeux at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, and the later assemblage and expansion of this work by biologist and Nobel laureate Gerald Edelman in San Diego into what is now referred to as 'Neural Darwinism' or 'Neural Selectionism', has provided new tools with which to understand the important role played by culture in the configuration of the architecture of the central nervous system. This theory, or as it is sometimes called, the 'Theory of Neuronal Group Selection', has three main tenets: developmental selection, experiential selection and reentry. Developmental selection describes the ontogeny of the embryo as an interaction between its genotype and the circumstances of its prenatal environment. Events occurring at the microscopic level, such as cell division, migration, differentiation and plastic modification, create what Edelman refers to as the primary repertoire. This term describes a dense and variable population of neurons with complex branching patterns that create extensive neural connections.7

Experiential selection is defined as the period just prior to birth and continuing throughout life, in which the diverse and variable population of the primary repertoire is pruned and sculpted by the environmental context to which the human being needs to adapt. Most changes, however, take place in the early years and are linked to what is referred to as ëneural plasticityí ñ the ability of neurons and their synapses and dendrites to adapt and change as a result of experience. Most importantly, according to Edelman, Experiential selection does not, like natural selection in evolution, occur as a result of differential reproduction, but rather as a result of differential amplification of certain synaptic populations8. Further, those neurons, neural networks or assemblages of neurons, and their dendritic and synaptic components that are most often and intensely stimulated, will acquire more efficient means of information transmission, thus enabling them to outmanouevre those neurons and neural networks that donít. In other words, as a result of being repeatedly excited by recurrent and repetitive external stimuli, these neurons develop firing patterns that have increased efficiency and specific tuning, and as a result are therefore likely to be favoured over other neurons and networks in future encounters with this stimulus.9

However, neurons and neuronal networks do not fire in isolation; they are part of large complexes that are together called out by complex stimuli. They could be part of abstract assemblages of stimulation, such as a billboard one might find in Times Square in New York or Piccadilly Circus in London, with its flashing lights, smoke rings, video screen, text messages and speaking voice telling you to smoke Camel cigarettes As eminent cognitive psychobiologist D.O. Hebb has so astutely stated, 'Neurons that fire together wire together'. They form greater firing efficiencies collectively, and form other alliances with other networks similarly excited and predisposed.

Reentry, the third part of the neural selectionist triad, allows for the synchronisation of neural events occurring in circumscribed and widely disparate areas of the brain. It plays a role in binding together these networks, some of which are broadly distributed throughout the brain, through its dynamic influences. As a result of this cooperation, even a partial trace of the original stimulus, by exciting a small number of neurons in a section of the complex web of neurons, can excite all the neurons in the network. Sharing of inputs in this manner allows for the repetitive stimulation of the network, which results in greater efficiencies for all the individuals in the whole group. It also gives the network advantages, in the competition for neural space, over other neural groups not thus stimulated.

Those neurons and neuronal groups that are less stimulated either find other targets to connect with, or undergo a mode of cell death called apoptosis: the process by which neurons that fail to find their targets degenerate and then are phagocytised (eaten up or absorbed by other neurons). In simple nervous systems, apoptosis plays a major role in pruning the least-used synaptic connections being selectively destroyed, while the mostused are retained. However, in more complex systems like the cerebral cortex of humans, it plays a minor role. "[I]t appears that apoptosis is a more important factor in simple systems such as the spinal cord motor neurons, where about fifty percent of the neuronal population is wiped out than in more complex systems like the primate cerebral cortex where it occurs in less than twenty percent"10. In these systems, the abundance of potential sites for alternative connectivity in the cerebral cortex may alleviate the need for cell death.

So far, this is a story of pruning and subtraction. It only partly describes the data on brain development and evolution, which shows that the brain mass gets larger instead of smaller with age, and that different parts of the brain grow at different rates. Neural Constructivism sees development as a progression in representational complexity. It appears to involve both selective elimination as well as considerable growth and elaboration.11 Studies by Greenough and Chang12 and Coleman et al13 have found that the degree of correlation between the firing of groups of dendrites in the receiving part of a neuron, rather than simply the presence of activity, was essential for the production of dendritic complexity and growth. What this means is that the secondary repertoire the primary repertoire pruned by experience goes through a dynamic change in which those selected neurons undergo a further transformation. They continue to be stimulated by correlated activity, which may also correspond to correlated relationships in the realimaginary- virtual interface, with other neurons which are coding for similar stimulation complexes; and the connectivities thereby multiply and grow (here I am using the word 'virtual' to refer to virtual reality, not the virtual as described by Deleuze in relation to the actual, in his account of ontological parameters).

Neuralbiodiversity and Cultural Determinism

Culture is in a constant state of transformation as it responds to a changing milieu, determined by the cumulative effect of a multitude of immaterial relations that are each in a state of unrest. Each of these relations mutates within a rapidly evolving context of new possibilities for example, in relation to the speed of information transmission and develops new vocabularies and systems of meaning to accommodate those changes. Then, individually or together with the other changing relations also affected by these mutating conditions, they create new dynamic patterns of flows that impact culture. Sociological conditions, political intrigues and scandals, global economic depressions, conditions of psychological instability, historical reinvention, spiritual revivals all of these operate together to transform the context in which culture operates; and, in some cases, operate together upon culture itself. This flux creates new pressures on the system of culture, producing subsequent instabilities.

These instabilities are the result of noise produced by certain incompatibilities of coded information between the existing cultural system and the new flows of information it attempts to incorporate. To respond to this crisis of assimilation, culture creates new technologies. Here I would like to describe in detail one such technology, the optical; I confine myself to this in the interest of time and clarity, although similar changes are taking place in the auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile sensorial realms as well.

Optical technologies can be divided into two groups. First, projective creative optical technologies, examples of which are the camera obscura, camera lucida, photographic camera, stereo camera, cinema, virtual reality and, most recently, intelligent media. These devices help create the world as a projective interface to be inspected by the organic system of the eye and brain; as such, this eye-brain link produces the plastic mimetic configuration of the noumenal/phenomenal world. As is explained further in the essay, the eye-brain apparatus is a plastic and selected entity in a constant flux between being and becoming, a being and becoming that is co-evolving with the mutating conditions of the world. It is the relation between what I term intensive technologies (discussed later in this essay), and the cultures they attempt to redefine spatially and temporally: redefinitions that lead to new forms of linkages in the tectonic substrate of culture itself. I call these linkages 'cultural bindings'; and it is this binding of cultural artefacts, for instance, that leads to new networks of meaning within that culture. This cultural binding leads to intensely stimulating cultural networks that, as we will see, may sculpt neural networks preferentially (I use the word ìintenseî here to mean a very strong stimulus, as well as one which is non-linear, folded and rhizomatic in its spatial-temporal dimension. This latter quality is what makes such stimuli powerful agents of neural excitation). It is this fundamental relation between cultural and neural networks that defines what I am calling Cultural Determinism.

The evolution of projective optical technologies has for decades inspired artists, designers and architects, who were awed by the new kinds of images and processes that these machines made possible. In her description of 'La Fenêtre en Longueur', a drawing Le Corbusier made at his parents house on Lake Geneva, architectural historian and critic Beatriz Colomina states that the window glass is superimposed on a rhythmic grid that suggests a series of photographs placed next to each other in a row, or perhaps a series of stills from a movie14. This is an instance of photography and cinematography influencing the way the architect, in his desire to respond to these new optical possibilities afforded by cinematic time and space, reinvents the materials of his trade, glass and window, in a way that re-enacts and re-maps the experience of cinema onto the experience of architecture. We will see shortly the implications of this effect on other forms of visual culture, and their summated affect upon the nature of embodiment.

Invented in parallel with these projective technologies are introspective technologies. The word 'introspective' can have psychological meanings related to the investigation of the self, as in looking into oneself or knowing oneself; but in the context of this essay, I am referring to instruments that probe the body in order to understand its own changing anatomical and physiological conditions. Introspective technologies may in the future help us to see at the functional, dynamic, synaptic and neuronal-net level, on which the effect and residue of events in real/imaginary-virtual space over time can be appreciated. This kind of brain mapping is beyond our reach today. However, recent theories that attempt to make sense of the ways the brain works have begun to leave strict hierarchical descriptions in favour of ones that are non-hierarchical.15 For instance, neural complexity in relation to subjectivity is now being studied at the level of collectives of neural circuits that display patterns of emergence of large-scale integration.16

Of the many new devices invented that enable culture to visualise itself, only a few are really relevant; and these, as a result of their widespread use and dissemination, help define and optically describe that culture. Perspective was the best visual analogy with which to describe the sociological, psychological, economic, historical and spiritual conditions of the Renaissance; new media is the best way to depict those same conditions today.17 This is not to say that one excludes the other. In fact, the genealogy of optical instrumentation is a history of one technique subsuming the qualities of its predecessors, followed by a moment of unease in which structural rearrangement leads to a mutation in its form and operation, and then to the invention of a new device that can be adapted more adequately to the conditions at hand. We are reminded of communications theorist Marshall McLuhan's idea of 'remediation', in which the content of any medium is always another medium.18

I suggest here that an analogical process of remediation is occurring in the brain as well. The co-evolutionary phenomenon I have been alluding to is more than simply a

selection of neural tissues: it is an evolution of the processes through and by which they operate. Phylogenetic changes are slow changes, the result of genetic mutations: All the old control systems must remain in place, and the new ones with additional capacities are added on and integrated in such a way as to enhance survival. In biological evolution, genetic mutations produce new cortical areas that are like new control systems in the power plant; while the old areas continue to perform their basic functions necessary for the survival of the animal, just as the older control systems continue to sustain some of the basic functions of the power plant.19

Older systems of the brain form the basic foundations for the new capacities of the organ as it evolves.20 This has been discussed earlier in the essay with regard to the

primary repertoire, which is the end result of millions of years of evolution. Its variability is to a certain extent determined by all the changes recorded in the genotype, and slowly refined by natural selection.21 I refer to this variability as neuralbiodiversity. This condition, hospitable to and augmented by the mechanisms of neural plasticity, enables the rapid changes of experiential selection to take place, as well as those of epigenesis the development of an individual and/or the external environment as a result of interaction between an individualís genes, external environment and internal environment.

These rapid generational changes in context of genetic drift and Baldwinian evolution (which is based on the fact of phenotypic plasticity, the ability of an organism to adapt to its environment during its lifetime, and which emphasises the fact that the sustained behaviour of a species or group can shape the evolution of that species) can become incorporated into the genome. The anthropologist Terrence Deacon delineates this as the mechanism by which we acquired language, and for which a special area of the brain was developed.22 Deacon explores the means by which language evolved as a cultural entity. He sampled a population of humans with a variable innate capacity for the acquisition of language. As language produced real advantages, those whose brains were more receptive to the acquisition process in the end gained a selective sexual advantage, and through their descendants produced a population of what he now calls homo symbolicus. Similarly perhaps, new technology ñ through creating new types of images, sounds, feelings and hapticities with intensive spatial and temporal logics has produced different forms of cultural networks and binding. In the end, using a similar logic to that of Deacon, new forms of humanity could be produced. The new habits we now see in the children of the Egeneration, who appear to have multiple or split attentions, is one example of such affect.

In other words, each new generation has a living brain that has been wired and configured by its own existence within the mutating cultural landscapes in which it lives. These new conditions allow for new kinds of images, new thoughts, new ideas that are transmitted and embedded in cultural forms of representation. As such, the history of this transformed representation forms a kind of cultural memory or cultural heredity, which has its own rules and regulatory patterns of evolution, that are different but symbiotic with Darwinian evolutionary paradigms of selection, subtraction and deletion. It is a system of memory that evolves as the result of the Bergsonian mode of 'creative evolution', which is neither mechanical nor teleological, and does not represent evolution as conditioned by existing forces or by future aims; it is additive, and concerns the ways and means that the constantly transformed context provides a backdrop for the constant re-evaluation and reformulation of cultural ideas. These ideas are alive, but pulsate at different amplitudes and frequencies in the web of cultural meanings, depending on the ratiomatic and proportional distribution of immaterial relations that create that context.23

By ratiomatic, I imply that cultural meanings are virtual and in flux. I am here referring to 'virtual' in the Deleuzian sense of a repository of possible meanings that are made actual by, for instance, the relative opposition between transcendence and immanence, this difference enabling dualistic categories, Cartesian and otherwise, to be maintained. In the context of my argument, virtual implies the set of immaterial social, political, historical, psychological, economic and spiritual relations that create the human subject's overriding context at a particular moment. The inherent virtual meanings are the results of complexes of cultural binding that create nodes of varying intensities in the networks of relations. Some of these nodes are thick and strong, while others are weak and thin. Their overall distribution in the 'plane of immanence' is their ratiomatic identity, and it changes all the time. But subtle neural changes are continuously initiated by the variable conditions of this cultural milieu. Through its capacity to reorient and seek out alternative sites for connectivity, the brain thus sculpted is able to bind and suture itself to contextual peculiarity and difference. This cultured brain can also be properly termed the intensive brain.

In a system of network conditions that are pulsating and immanent, and therefore available only at certain times, what is present at any one moment will reflect the specific combinations of entities that are existent at the time of that reception. However, what is existent is dependent on a specific context in which these networks are embedded, and which is different for each network. Thus, each context creates a ratiomatic flow of immanent cultural meanings. This cultural memory then becomes the framework through which the cultured brain is produced. When each observer dies, those neurological changes that defined his or her experience and relationship to his specific generational moment within visual culture dies as well. Only in very unusual circumstances will these experiences find their way into the genome, as in the example of language. However, that generation's cultural effect is retained in traces within that cultural habitus, awaiting a new generation of brains on which to mould new kinds of neural relations, in the end creating new types of subjectivity. In other words, a kind of cultural somatic mnemotechny is disseminated in forms of literature, visual art, architecture and design. Separately and together, as these practices evolve they create new forms of cultural attention.

Cultural attention delineates the subset of cultural forms and relations that call out to the developing brain, through its use of images, forms of language or social contingencies that in the end are important in the processes of sculpting the brain. It too is evolving, and becoming ever more sophisticated as its forms of spatiality and temporality become linked to ever more sophisticated forms of media. These new forms are beginning to adapt and synchronise themselves to those operating at the level of neural networks. This process is called visual and cognitive ergonomics, and will be addressed later in this essay. At the moment, it is critical to re-emphasise that this development is the result of the coincident effect of the evolution of optical and haptic projective and introspective technologies.

Recently, as a result of digital technologies, there has been a transformation of the conditions of culture itself, which has implications for the history of cultural attention. I am referring to the shift from an extensive to an intensive culture. Its precursors could be first found in earlier non-narrative film practice, exemplified by Soviet director Dziga Vertov's Man With a Movie Camera (1929) and Italian director Luchino Viscontiís Obsession (1943). Film scholar Donato Totaro aptly sums it up: ìIn the time-image, which finds its archetype in the European modernist or art film, characters find themselves in situations where they are unable to act and react in a direct, immediate way, leading to what Deleuze calls a breakdown in the sensory-motor system. The image cut off from sensory-motor links becomes a pure optical and aural image, and one that comes into relation with a virtual image, a mental or mirror image24.

No longer tethered to the restrictions of the body and its narrative context of action and perception, the time-image is free to circulate according to other possible temporalities, some of recursive feedback on the body, producing new potentials and becomings. According to contemporary philosopher Manuel De Landa, the term extensive time may be applied to a flow of time already divided into instants of a given extension or duration, instants which may be counted using any device capable of performing regular sequences of oscillations. These cyclic sequences may be maintained mechanically, as in old clock-works, or through the natural oscillation of atoms, as in newer versions25 Intensive time, however, is characterised by nested sequences of temporality that form complex and multiplicitous relations with each other. A good example is found in the of the genomic regulatory system described by theoretical biologist Stuart Kaufman:

The network, in so far as it is like a computer programme at all, is like a parallel processing network. In such networks, it is necessary to consider the simultaneous activity of all the genes at each moment as well as the temporal progression of their activity patterns. Such progressions constitute the integrated behaviours of the parallel-processing genomic regulatory system.26

Thus, as we learn more and more about the brain and how it works, and as we begin to apply the power of computational technologies to answer some of the questions

concerning its methods, we begin to see that neuro-scientific narratives based on linear modes of explanation are giving way to non-linear descriptions.

The Phylogeny of Projective Optical Technologies

One could hypothesise that the genealogy of optical instrumentation from the Renaissance to the contemporary moment is a story that recounts the history of the changing meanings of time and space. Photography most effectively reinvents and experiments with space, while cinema, building on this spatial practice, added new ways to deal with temporality. It animated and continues to animate space. Through the techniques of analog fast-cut editing, embedding fast-forward and reverse effects into narrative, and silhouetting as a means to illustrate the past, cinema reinvented the interpretation of time. As Hungarian artist and photographer L. Moholy-Nagy remarked with regard to Vertov's The Camera Eye (1924):

The combination of all these elements in their astonishing interchangeability revolutionises the customary visual as well as conceptual processes. It produces a

completely new timing of perception based upon the translation of physical motion into pictorial motion, also the translation of the initial action into an objectively observable process viewed by the acting persons themselves. Though this may appear at first bewildering, one must acknowledge that a new code of space-time perception is in the making.27

This experimentation of cinema with time does not occur in a vacuum, but is part of a network of conditions occurring in other fields similarly affected by concepts and interests involving temporal phenomena. Marcel Proust's À La Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time), a seven-volume semi-autobiographical novel published between 1913 and 1927, Sigmund Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Albert Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity (1905) and his General Theory of Relativity (1915), and Henri Bergson's Matter and Memory (1896) these paradigmatic writings all dealt with different experiences and formulations of time.

The field of new media, as it grew out of cinema and television, created a digital time and space: a space and time that is now folded, intensiveí and rhizomatic. Powerful

information and communication technologies, such as the internet, undermine serial, extensive ideas of time and space. According to information cartographers Martin Dodge and Robert Kitchen, intensive technologies disrupt traditional forms of cultural and social interactions in critical ways: they promote a mode of global culturisation at the expense of local customs and traditions; they facilitate what has been termed incidental outsiderness, meaning that people live in multiple locations; and they create an alternative sense of identity, one that is fluid, mobile and disembodied. Thus, community that had formerly been dictated by factors of presence and place is now formulated on the basis of interests rather than on location28.

But these are not the only effects. In each case, these network relations leak out of the specificity of optical media into design, fashion and architecture; and, in the end, they

radically alter the visual and haptic landscape. Can anyone imagine the folded, wandering, gestural movements of the Guggenheim Bilboa without Computer Assisted Design programmes, or the idea of the rhizome of Gilles Deleuze without the Minitel? The same visual landscape that, as we will see later, will help select the brain and affect identity. Linked together, these technologies create parallel systems of temporality that simultaneously manifest in time and space, like the genetic regulatory system or the model of the brain using the process of reentry, broadly defined as the synchronisation of neural events occurring in circumscribed and widely disparate areas of the brain.

Photographic spatiality, disrupted, linear and non-linear cinematic time and space, and digital, co-extensive time and space are all now folded together through the transductive force of binary code, which is assimilative. Remediation itself cannot be seen as anything but nomadic, non-linear and recursive. One media does not flow directly into another in a linear and positivist way, but is a series of jolts, digressions, regressions, informal mixings and bricolage. The material specificity of modernism has relinquished its hold on the imagination in todayís world of pervasive symbiotic systems characteristic of the postmodern condition. The result is a grand tapestry of time and space that has resulted in new combinatory possibilities and, by extension, new possibilities for thought and creativity. As these nested relations redefine objects and images, they create landscapes of meaning; these visual ensembles are sampled and processed by the intensive brain.

Brain / Mind / World

The complexities under discussion here are precisely defined by philosophers of science Franciso J. Varela and Evan Thompson:

The nervous system, the body and the environment are highly structured dynamical systems, coupled to each other on multiple levels. Because they are so thoroughly enmeshed biologically, ecologically and socially ñ brain, body and environment seem better conceived of as mutually embedding systems than as externally and internally located to produce (via emergence as upwards causation) global organism-environment processes, which in turn may affect (via downward causation) their constituent elements.29

The genealogic relations of optical technologies, both projective and introspective, contain a number of meta-genealogic relations that influence the physical constituents of

the instruments themselves, how they are made, the images they produce, and the effect these have on the brain and mind. I am referring to a number of processes categorised as visual and cognitive ergonomics30. These two terms refer to the way that technology, combining the knowledge of neuroscience and physiological psychology with the advanced application and utilisation capabilities of computing and recent advances in special effects, has created visual images that are more powerful then naturally occurring ones, with more enhanced potential for first calling out, and then selecting, the nervous system.

These processes employ and utilise sophisticated fields of what urbanist and theorist of technology Paul Virilio calls ìphatic signifiersî. The word 'phatic' shares the same root

as 'emphatic' (Gk. emphanein, to exhibit/display): it means something that forces you to look at it. The phatic image a targeted image that forces you to look and holds your attention is not only a pure product of photographic and cinematic focusing. More importantly it is the result of an ever-brighter illumination, of the intensity of its

definition, singling out brighter only specific areas, the context mostly disappearing into a blur.31

I use the expression ìfields of phatic signifiersî to stress that these stimuli are linked up in large conglomerates of stimulation. Think for a moment of ëbrandingí. The brand is only one part of large landscape of interconnected signifiers. Visual and cognitive ergonomics has been instrumental in the production of this ëbrandedí environment. It refers to an evolution of these practices as they develop in the real/virtual interface as well as the world of bodily experience. The dialogue of optical instrumentation, neurophysiologic research and, more recently, advertising and computerised special effects, has impacted the configuration of visual space in which brands are embedded. The visual landscape has become more textual, and thereby more comprehensible, to an intensive brain that has undergone analogous, although idiosyncratic, changes consistent with its own material substance, its convoluted gyri and sulci consisting of millions of neurons, glia and blood vessels. As a result of experiential selection, new types of neuronal configurations leading to new patterns of neuronal discharge have emerged, reflective of this evolving visual space and time.

Phatic stimuli are produced according to the rules of visual and cognitive ergonomics, and as such have greater attention-grabbing qualities than those stimuli not so engineered. The development of these stimuli traces a history of increasing sophistication and simulation between them. This history is punctuated by moments of competition with each other for the brainís attention, followed by moments of cooperation when certain of these stimuli link up to form networks of stimuli, giving them emergent abilities far greater then they had before, in their isolated states. What emerges is an ecology of phatic forms, the human brain being its interface.

The neuro-anatomical and neuro-physiological condition of the living brain reflects its epigenetic experience. Epigenesis involves the processes by which genetically prescribed forms are altered by interaction with their environment, be it pre-, peri- or post-natal. The conditions of the developing brain, just like the conditions of the world, create specific environments that affect populations of neurons in specific ways that have crucial consequences for its neural architecture. That experience, having been recently dominated by the phatically charged, artificially constructed, cultural domains into which it is born, will reflect a condition generated by intensive non-organic fields of stimulation. (As mentioned earlier in this essay, one could make a similar argument for other sensorial domains.) This condition is one in which naturally derived, organic stimuli and signs, such as trees or our own naturally conditioned feelings, have difficulty competing with phatic entities for the mind's attention. The story of Thomas in my essay 'Blow-up: Photography, Cinema and the Brain' is about this problem.32

If one superimposes the effect of global capitalism on this perceptual system, one begins to understand its staggering proportions; for it has the potential of producing and

disseminating these stimuli worldwide, and to sometimes bizarre excess. Just think of the McDonalds brand, or the power of CNN. These highly engineered sign systems are

distributed worldwide with incredible intensity. They have, in fact, become new media objects, according to cultural theorist and sociologist Celia Lury. A key theme in her analysis is the idea that the brand acts in the market like the interface of a computer: it is a mobile, dynamic and responsive framing of communication33. She adds: "Central to the interactivity of the brand are certain practices in marketing which function in an analogous way to programming techniques in both broadcasting and computing. The most significant example is the feedback loop many marketing practices act like feedback loops of a computer programme"34. Products differentiate according to complex open autopoeitic systems self-limiting, self-generating, self-organising, self-maintaining and selfperpetuating (much like the cell) ñ and through practices like marketing mix, with its model of the 4 Ps': product, price, place/distribution and promotion. Consumer surveys probe user desires, needs and wants, and link these to the use of the product as a marketing tool; this data enables the producers to finally create a kind of super-sized, über meta-object, a phatically compelling entity that is constantly becoming as it competes in a field of similarly differentiating meta-objects for the observer's attention.

The brand progresses or emerges in time in a series of loops, an ongoing process of (product) differentiation and (brand) integration. It thus comprises a dynamic sequence or series of loops that entangle the consumer, Lury concludes.35 Brands also form corporative relations with other brands. For instance, the Coca Cola, Disney and Mars

Corporations have joined up to form networks of brands that interconnect both synchronously (they all occupy one space simultaneously and react in a dynamic and nonlinear fashion to create super-sized desire) and diachronously (they link to the history of other advertising campaigns in which, separately or together, they attempt to influence choice, perhaps in the parents of their target group, young children; this represents a kind of internal marketing in which the brand influences new consumers, children, by appealing to the nostalgia of the parent).

Brands are a distinctive form of phatic signifiers, particularly when they are produced with the use of special effects, or when they are embedded as products used in popular

movies. They become attentionally intensified when they are linked up to global campaigns in which they participate in other global phenomena, such as the global flows of money, people, ideas, raw materials; and through which they interact with local food, languages and cultural customs. These emerging properties, as they are expressed in the global context, can compete effectively for the attention of the global brain.

In a brain that has been selected for through the operation of neural Darwinistic and neural constructivist pressures, the spatial configurations of neurons and networks and

their non-linear, dynamic neural signatures manifest as synchronous oscillatory potentials; they reflect the influence of this complex, competing, artificially created network of phatic signifiers that dominate the contemporary visual landscape. Drawing attention to these processes of binding and dispersal, I propose that as the systems of technical/cultural mediation become increasingly more folded, rhizomatic and cognitively ergonomic, they evolve to more closely approximate the conditions of temporal transaction that sculpt the intensive brain.

I would also hypothesise that there exists an envelope of possible formulas of output from the brain, a kind of virtual potential in the Deleuzian sense. As intensive culture evolves into more complex formations, it produces new dispositions that, when selected and coded by the brain, unlock that potential.

The brain is a becoming machine. The paradigms of neural plasticity and neural Darwinism provide the crucial frame for its continual renewal but also perhaps for its

eventual subjugation.

NOTES

1. Melanie Wells. ìIn Search of the Buy Buttonî. In Forbes Magazine (1 September 2003), pp. 62-70.

2. But the first zone of the power centre is always defined by the State apparatus, which is the assemblage, that effectuates the abstract machine of molar overcoding: the second is defined in the molecular fabric immersing this assemblage; the third by the abstract machine of mutation, flows, and quanta. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (Continuum, 1988, New York) p. 227.

3. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri. Empire (Harvard University Press, 2000, Cambridge).

4. Ibid., p. 23. Power is now exercised through machines that directly organise the brains (in communication systems, information networks, etc.) and bodies (welfare systems, monitored activities) toward a state of autonomous alienation from the sense of life and the desire for creativity.

5. Ibid., p. 24.

6. Ibid., p. 33. The communication industries integrate the imaginary and the symbolic with the biopolitical fabric, not merely putting them at the service of power but actually integrating them into its very functioning.

7. Gerald Edelman. The Remembered Present (Basic Books, 1989, New York), p. 45.

8. Ibid., p. 46.

9. From that process of competitive selection in the primary repertoire of cell groups, which is a process fundamentally based on variability, correlation, and connective re-entry, a secondary repertoire of neuronal groups will emerge. They will form a new representational map. The neuronal groups of this second repertoire, that is, of the newly formed map or network, will subsequently respond better to the individual stimuli that formed it. Further, the network as a whole will recognise those stimuli by responding to them categorically. Thus, by the selective process, the secondary network will have become a more effective representational and classifying device for perception, memory and behavior than the original, primary repertoire of cell groupsî. See Joaquin M. Fuster, Cortex and Mind: Unifying Cognition (Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 38.

10. A central hypothesis underlying remediation and enrichment programmes is that the brain is more malleable during infancy and early childhood than later in life. This malleability leads to an increased capacity for learning, which in turn provides an opportunity for the improvement of cerebral functioning that cannot be reproduced to the same extent or with the same ease later in life. This property of the immature brain is referred to as neural plasticity. See Peter R. Huttenlocher, Neural Plasticity (Harvard

University Press, 2002, Cambridge), p. 53.

11. S.R. Quartz and Terrence J. Sejnowski. The Neural Basis of Cognitive Development: A Constructivist Manifesto. In Behavioral and Brain Sciences 20 (4), pp. 537-96.

12. W.T. Greenough and F.L. Chang. Dendritic Pattern Formation Involves Both Oriented Regression and Oriented Growth in the Barrels of Mouse Somatosensor Cortex. In Brain Research 471, pp. 148-52.

13. P.D. Coleman et al. ìSpatial Sampling by Dendritic Trees in Visual Cortexî. In Brain Research 214, pp. 1-21.

14. Beatriz Colomina. Privacy and Publicity, Modern Architecture as Mass Media (MIT Press, 1998,nCambridge), p. 139.

15. Varela, F.J. et al. The Brainweb: Phase Synchronisation and Large Scale Integration. In Nature Reviews, Neuroscience 2, pp. 229-39 (2001).

16. M. Le van Quyen. Disentangling the Dynamic Core: A Research Programme for Neurodynamics at the Large Scale. In Biological Research 36, pp. 67-88 (2003).

17. Bolter and Guisinís theory of remediation proposes that ìthe history of media is a complex process in which all media, including new media, depend upon older media and are in a constant dialectic with them. Digital media are in the process of representing older media in a whole range of ways, some more direct and transparent than others. At the same time, older media are refashioning themselves by absorbing, repurposing and incorporating digital technologiesî. In (eds.) Lister, Martin et al, New Media: A Critical Introduction (Routledge, 2003, London), p. 55.

18. Ibid., p. 78. So, for McLuhan, the importance of a medium (seen as a bodily extension) is not just a matter of a limb or anatomical system being physically extended (as in the hammer-as-tool sense). It is also a matter of altering the ratio between the range of human senses (sight, hearing, touch, smell), and this has implications for our mental functions (having ideas, perceptions, emotions, experiences, etc.).

19. John Morgan Allman. Evolving Brains (Scientific American Library Series, 1999, New York), p. 41.

20. There are, grossly speaking, two kinds of nervous system organisations that are important to understanding how consciousness evolved The first is the brain stem together with the limbic (hedonic) system, the system concerned with appetite, sexual and consummatory behaviour and evolved defensive behaviour patterns. It is a value system; it is extensively connected to many different body organs, the endocrine system and autonomic nervous systemÖ It will come as no surprise to learn that the circuits in this limbic-brain stem system are often arranged in loops, that they respond relatively slowly (in periods of seconds to months), and do not consist of detailed maps. They have been selected during evolution to match the body, not to match large numbers of unanticipated signals form the outside world. These systems evolved early to take care of bodily functions; they are systems of the interiorî. See Gerald Edelman, Consciousness: The Remembered Present, in (eds.) Sporns, Olof and Giulio Tononi, Selectionism and the Brain (Academic Press, 1994), p. 111.

21. Personal conversation with Gerald Edelman.

22. Selection pressures affecting language must be considered as nested within one another to the extent that language evolution is nested in biological evolution. On the human side of this equation, the processing demands of symbolic reference, symbolic combination and symbolic communication in realtime provide novel selection pressures affecting the brain and vocal tract. As the language-mediated niche (the symbolic cultural environment) became more and more ubiquitous in human prehistory, these selection pressures would have become correspondingly more important and powerful, producing evolutionary changes in these structures in response. On the language side of this equation, the humanderived requirements of learnability, automatisability, and maintaining consistency with the constraints of symbolic reference provide selection pressures that affect language structures. See Terrence Deacon, Multilevel Selection and Language Evolution, in (eds.) Weber, Bruce H. and David Depew, Evolution and

Learning: The Baldwin Effect Reconsidered (MIT Press, 2003, Cambridge).

23. Very different, in our opinion, is the kind of definition which befits the sciences of life. There is no manifestation of life that does not contain, in rudimentary state, either latent or potential the essential characters of most other manifestations. The difference is in the proportions. But this very difference of proportion will suffice to define the group, if we can establish that it was not accidental, and that the group, as it evolves, tends more and more to emphasise these particular characters. In a word, the group must not be defined by the possession of certain characters, but by its tendency to emphasise them. See Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution (Dover Publications Inc., 1911).

24. Donato Totaro.Gilles Deleuze's Bergsonian Film Project. Offscreen, 31 March 1999.

25. Manuel De Landa. Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy (Continuum, 2002, New York/London).

26. Ibid., p. 58.

27. L. Moholy-Nagy. Vision in Motion (Paul Theobald and Co., 1965, Chicago) p. 280.

28. Martin Dodge and Rob Kitchin. Mapping Cyberspace (Routledge, 2001, New York).

29. See Francisco J. Varela and Evan Thompson, ìNeural Synchrony and the Unity of Mind: The Neurophenomenonological Perspective, in (ed.) Axel Cleeremans, The Unity of Consciousness: Binding, Integration and Dissociation (Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 279.

30. For a detailed analysis of these terms, see Warren Neidich, title essay in Blow-up: Photography, Cinema and the Brain (DAP, 2003), pp. 22-30.

31. Paul Virilio. The Vision Machine (Indiana University Press, 1994, Bloomfield), p. 14.

32. "Blow-Up" is the story of the ìmutated observerî: one whose neural networks have been sculpted by artificial stimuli to the point that he has become what I call cyborg-ised. Thomas, who plays the role of the fashion photographer David Bailey, has two types of memory. One is the result of his own experiences; the other the result of the memories of the photographs he has taken. As the photographs are more phatic, they compete for the brainís neural space more effectively. He loses touch with his own feeling and memory when these are not supplemented by photographic documentation.

33. Celia Lury. Just Do What? The Brand as New Media Object, inaugural address given at Goldsmiths College, London, 2004.

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

Pierre Molinier and the Phantom Limb

Fetish

The original definition of the fetish finds its roots/routes in the religious practices of so called "primitive" societies. The fetish was defined as a menagerie of objects connected through their properties as magical charms. In nineteenth century Europe the definition of fetish evolved into anything that was irrationally worshipped.

It was not until the seminal work of Alfred Binet (mostly known for his I.Q. test) that the fetish became linked to sexual practice. “Normal love is the result of complicated fetishism. Pathology begins only at the moment where the love of a detail becomes preponderant.”(3) Kraft-Ebing drew attention to the idea of pathologic erotic fetishism in which the fetish itself becomes the exclusive object of sexual desire, “while instead of coitus strange manipulations of the fetish become the sexual aim.”(4) Today the American Psychiatric Association in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual defines fetishism as recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges or behavior involving the use of non-loving objects, inanimate or animate material which can be hard or soft.(5)

But the subject of fetishism is much more complex than the above definitions would imply, and in order to discuss Pierre Molinier a slight digression to review pertinent literature is needed.

Freud wrote in 1905 that the fetish was an unsuitable substitute for the sexual object that serves to disavow knowledge of the differences between the sexes. (6) Five years later, in "Leonardo Da Vince and Memory of His Childhood", 1910, he reiterated that the fetish is linked to intense castration anxiety in men.(7). Agreeing with Kraft-Ebing he organized the fetish around the notion in which an inanimate object is used in an obligatory and fixed manner in order to attain sexual gratification. The choice of the fetish is a substitute for the absent female phallus that the young boy discovers is lacking in his mother. Thus the pieces of underclothing, i.e., garters, silk stockings, fur, which are so often chosen as a fetish “crystallize the moment of undressing.” For Freud, in 1910, the object of choice is “merely a substitute symbol of the woman’s penis which was once revered and later missed.”(8) “The child becomes fixated on some safer object, which aids in warding off the feared knowledge of the mother’s castrated state.”(9)

A complementary theory to castration anxiety is separation anxiety which is suffered and defended against in childhood.. Through the creation of illusion, and the symbolic gesture of representing the mother through the fetish object, some state of union, or reunion, with the absent mother is preserved. Louise Kaplan notes in Female Perversions: The Temptation of Emma Bovary that “the little boy whose childhood curiosity, fantasies, anxieties and wishes lead him to endow his mother with a substitute penis is constructing only a temporary, elusive fantasy...that the adult fetishist will concretize into a shoe or fur piece... As Freud was the first to insist, the extravagant theories of little boys may be outgrown and forgotten but they are never entirely given up.”(10)

Although Bak, in 1953, states that the “fetish undoes the separation from the mother through clinging to the symbolic substitute.”(11) he understands its fundamental function is still to alleviate castration anxiety. The child caught in the Oedipal triangle fears the father who he fantasizes is the culprit of the misdeed. To maintain his relationship with his mother and dissuade bodily damage he takes the symbolic gesture of the fetish. Chassegunet-Smirgel join these two etiologies with a conception of illusion.(12)

Illusion for Freud is brought about by a defense--that of disavowal of threatened reality. The ego, which Freud described as that part of the psyche that mediates between the intense sexually motivating drives of the id and the socializing function of the superego, is thus split. On one hand, it has a reality function directed to real data and on the other, an illusionary scrim through which reality is filtered and adjusted. Thus the child attempts to maintain the illusion of the phallic mother; a mother that does not require him to fertilize her in order to maintain their social union. The fetish is the symbolic representation of mother as phallus. Mother then can continue her procreative function alone. She thus becomes, in a sense, a parthogenic hermaphrodite.

Parthogenesis being the ability found in certain insects, in which male and female attributes are maintained in one individual, where sexual intercourse is not necessary for procreation. Hermaphrodite describes an individual who maintains the sexual characteristics of both genders, male and female.

It is not a great theoretical jump to formulate a proposition for the “anal sadistic” component that J. Greenacre talks about in her 1979 paper, Fetishism. (13) Here the performance of anal intercourse is a later re-enacted form of earlier unaccomplished/inhibited intercourse.

The fetishist is involved in a self-fulfilling enactment of taking the mother into him physically and psychically. Never having made the concrete distinction between genital types, the fetishist’s illusions of childhood become recontrived as himself-mother. The hermaphrodite tendency thus becomes defined as the stultification of the ontogeny of psychic sexual dimorphism. The fetishist is looped in a virtual memoryscape. We will return to this theme in our discussion of Pierre Molinier, who as a fetish artist is described by Peter Gorson in The Artists Desiring Gaze on Objects of Fetishism: “The transvestite figure of the Shaman, which is one of the themes of Moliniers’ self-portraits, allows the artist to identify with the feminine body image of the woman (after Freud unconsciously that of the mother) with pleasure and without conflict, where in reality he should experience a threat to male, genital narcissism.(14)

Clothes as fetish object

The fetish object, as signifier, has specific characteristics such as smell, touch, color (typically black.) Bornstein, recalling a letter Freud wrote to Abraham, remarks on the centrality of “coprophilic olfactory qualities in shoes and foot fetishes.”(15)

Tough durability of the object is an issue because sometimes they are used harshly. Finally, the object is shaped like a body part, especially those involved in sexual encounters, while often it hides or encloses other parts.

Although many objects function as fetishes; masks, pieces of fur, handcuffs, etc., it is those related to the foot and leg that are most prevalent. Since this discussion centers on Pierre Molinier, and his proclivity for the foot and leg, it’s prudent that we focus on this part of the anatomy. According to Valerie Steele, “shoe fetishism emerged in the eighteenth century.”(16). Quoting Stephen Kern in his book “Anatomy and Destiny,” the high incidence at that time of fetishes involving shoes and stockings “further testifies to the exaggerated eroticism generated by hiding the lower half of the female body.” (17)